It is the Bangladesh-Myanmar border; the calm of the forest is broken by piercing sounds of gunfire and screams. Everywhere, people are on the run and she too trudges on, heavy, weary steps one at a time, trying to find refuge. She eventually makes it to the forests of Bangladesh only to be stuck indefinitely.

I am talking about an Asian Elephant or possibly a herd of Asian Elephants that entered Bangladesh through Myanmar. This scene, albeit imaginary, is set against the backdrop of August 25, 2017.

The Asian Elephants which entered Bangladesh for the forests of Teknaf and Ukhiya, did not plan on staying here for long. Because they remember their way out, come migration season they planned to make their way through the centuries-old elephant corridor (a trans-boundary migration route) through Ukhiya-Ghumdum, traverse through the forests of Myanmar, maybe stopover for a bit and then finally join others of their kind in Nyakkhongchori of Bandarban.

All the while shaping forests, discharging their duties as important seed dispersal agents and maintaining a balance in the ecosystem.

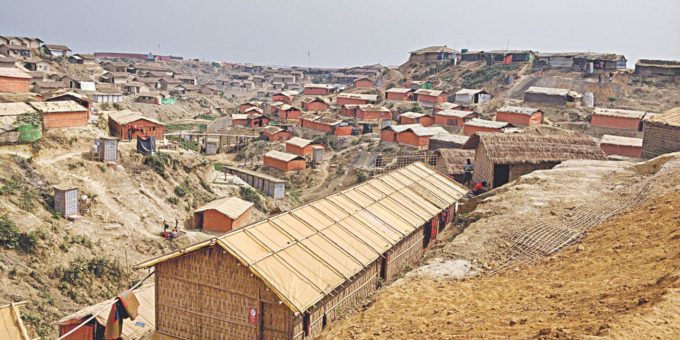

But that route is now closed and possibly forever sealed off by the now sprawling Kutupalong Rohingya refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar. The Rohingya refugees were the primary targets of a systematic persecution led by the Myanmar army which was dubbed as ‘ethnic cleansing’ by the United Nations.

In any war, humans bear the brunt of atrocities, but the Rohingya crisis that unfurled, spanning over decades of subjugation in Myanmar, has also brought forward a unique challenge for wildlife conservation in Bangladesh.

The Kutupalong camp, still growing due to a continuous trickle of Rohingya refugees, has completely blocked the corridor that connected the Asian Elephants to their larger range.

The Asian Elephant, which is critically endangered in Bangladesh, used this corridor to move from Ukhiya, through Ghumdum, to Myanmar and then re-enter Bangladesh through Bandarban for food, breeding and possibly to reach higher elevation during the rains, believe elephant experts.

“What this has done is confine around 35 Asian Elephants, both male and female adults and calves into a tiny patch of forest right by the Rohingya camps that is already under immense pressure for firewood and other resources,” says Amin.

Although the camp has existed in Bangladesh for many years and has received earlier waves of Rohingya refugees, the scale has never been this enormous, sudden, condensed or prolonged.

Despite billboards saying “Elephants move along this way” being in place around the corridor route since 2012, the Rohingya camps have expanded on this land, says Raquibul Amin, country representative of International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in Bangladesh.

“Of course, this was an emergency response and humanitarian reaction dictated that measures needed to be taken quickly and there really was no time to give much thought to anything else,” says Amin.

The camps are now an almost permanent fixture in the Cox’s Bazar South Forest Division landscape, once a core habitat of Asian Elephants.

For the overall population of Asian Elephants, too, this piece of forest has now become inaccessible, meaning the species which was largely concentrated around this range has lost yet another habitat.

Beside the camp are forestlands, around half the size of which is already deforested and the impact zone keeps increasing, says Amin.

Other experts also believe this forest in Cox’s Bazar is just not resourceful enough to sustain the engineers of the forest for long. They are keystone species: their dung is food for dung beetles, and other bottom-dwelling organisms and it also enhances soil fertility and their loss will simply cause a domino effect on the entire ecosystem.

There is a mutual dependency between elephants and the ecosystem it relies on and wiping them out will throw the complex food web out of balance.

The elephants have tried to make their way through the camps, not just once but many a time, resulting in the Rohingya people having to count further casualties—around 13 so far.

The reason elephants do this is because this they are behaviourally wired to always follow their traditional routes and if they find any obstacles within it, they try to break it, according to a report by the IUCN which surveyed elephant movement in the area.

But try as they might they could not penetrate the sea of tin-shed houses that have replaced the last Garjan forests that stood here. One particular video of a female elephant trying to make her way through the camp is particularly heartbreaking.

The animal is visibly under a lot of stress, she is seen moving her tail from one side to another, her ears flapping constantly as she tries to make sense of these new surroundings. She is chased by the residents of the camps, who are in fear of losing their new homes and possibly their life, to a confused, angry animal.

The elephant is not at fault; it is simply collateral damage in a conflict that happened across the border and that has caught it in a whirlwind too.

For now, UNHCR and IUCN are working together to mitigate this conflict, said Raquibul Amin. “We have trained Elephant Response Teams (ERTs) formed with the Rohingya volunteers to redirect the elephants if they try to enter the camp.” And since the beginning of the project, only two incidents of human-wildlife conflict have occurred, said UNHCR.

In response to my queries about any possible relocation of the camp area on the corridor or any possibility of it being viable for elephants ever again, UNHCR said, “Any future approach to elephants in the area is a matter for the national wildlife authorities.”

Meanwhile Jahidul Kabir, conservator of forests (wildlife and nature conservation circle) says

“The Bangladesh Forest Department has sent letters to the cabinet secretary and UNHCR through our ministry to relocate the camp area that falls on the corridor.”

“The camps are all on forest land. The elephant corridor was demarcated from before but we were not informed when the camps were set up,” says Jahidul.

The current arrangement seems partial to one party, despite the claim of mitigating ‘Human-Wildlife conflict.’

For these animals there are no other access routes to reach better forest patch in search of food or shelter. On one side is a water body blocking off access to the Chittagong Hill Tract forests and on the other, now stands the camp.

“Reju khal is blocking the other side of the forest, so this was their only way to access other forest lands,” said Dr MA Aziz, professor of zoology at Jahangirnagar University and working closely with the IUCN-UNHCR project.

This situation has also sparked fear of increasing the gender imbalance in elephants as male Asian Elephants have tusks while females don’t, thus making them easy target of poachers and this population is particularly vulnerable as the forest they are in is already not in good shape, according to MA Aziz.

“This inaccessibility has fragmented the dwindling elephant population in Bangladesh. The resources at their disposal in this forest are not enough to sustain the population for long,” said Jahidul.

Experts believe this fragmentation could eventually mean counting bigger losses for overall elephant conservation in Bangladesh.

This population, a sizeable chunk of the total 268 elephants (average) in Bangladesh, if it survives, will also possibly be subject to cases of inbreeding and this could significantly compromise their gene pool and cause diseases.

Jahidul Kabir is not hopeful for this population and believes they might not make it at all. The Chittagong-Cox’s Bazar-CHT range has the largest density of Asian Elephants in the country and this fragmentation means a stress on the entire elephant population in Bangladesh.

The refugees are cutting down trees from the forest for firewood and each day the edge of the forest moves a little farther away, the very same habitat housing the now enclosed elephant population, according to Raquibul Amin.

“It’s perplexing to see even at this time and age when the world is finally taking note of the need of saving megafauna such as Asian Elephants from extinction, we are pushing them closer towards it,” says Sayam U Chowdhury, conservation biologist based in Bangladesh.

“As conservation biologists our wins are very small, we count losses every day. To push wild elephants further into human-dominated landscape seems brutal. It is unfair to close corridors and possibly end up losing a big chunk of an already dwindling elephant population. Where we have so little forests as it is, to count losses in further forest cover can spell nothing but disaster for the Rohingya community, the host community and the wildlife community. I am glad to see that people are working tirelessly in order to find a balance here,” says Sayam.

Studies have shown war has another casualty apart from humans who are in the direct line of fire, a casualty that often goes overlooked: wildlife and wild places.

During Mozambique’s civil war from 1977 to 1992, giraffe and elephant herds in the Gorongosa national park shrank by more than 90 percent. Between 1983 and 1995, while the Lord’s Resistance Army terrorised Uganda, topi and roan, two species of antelope, were wiped out completely in the country’s Pian Upe reserve, according to a report in The Economist.

While humanitarian organisations have converged upon the coast town to help in the Rohingya crisis, there is little dialogue and mobilisation on the world stage for wildlife conservation and environmental protection.

Right now, there is no national programme in Bangladesh for the overall conservation of elephants.

As their threats—food shortage, habitat loss and fragmentation, and direct killing—continues to exacerbate all over the country, the question looms: Will our elephants be caught in this crossfire too?

Leave a Reply